Cutting Through the Curse of Dimensionality

Published:

This article explores the fundamental intuition of dimensionality reduction techniques.

Back when I was doing coursework in financial econometrics and data mining, the Bias-Variance Tradeoff was a constant theme. Essentially, Bias is the error that results from a learning algorithm making the wrong (often too simple) assumptions. Variance is the error that comes from the model being too sensitive to the specific fluctuations in the training data.

Their relationship is inversely proportional. When bias is high, variance is usually low, and vice versa. This means that when the error from algorithm assumptions is high, sensitivity to the training data is low. Basically when a model is too stubborn with simple assumptions, it becomes less reactive to the specific quirks and noise in the training data. While the ideal sweet spot is having both low bias and low variance, mathematically that is impossible. The goal is simply to find a delicate balance between them.

As a math guy, I find it helpful to visualize why this balance is necessary. In a regression case, the Mean Squared Error (MSE) decomposition is expressed as:

\[E[(y - \hat{f}(x))^2] = Bias[\hat{f}(x)]^2 + Var[\hat{f}(x)] + \sigma^2\]Since the relationship between bias and variance is inversely proportional, both errors must be kept low, otherwise, the overall MSE skyrockets!

In the context of dimensionality reduction, the aim is to find that balance specifically when variance is high. Extra dimensions must be cut to lower the variance without oversimplifying the model to the point that bias becomes a problem.

But when the bias is high, the method is not dimensionality reduction, typically it is feature engineering or increasing model complexity to help the algorithm actually capture the underlying patterns it is currently missing.

So dimensionality reduction is all about lowering the variance within the Bias-Variance Tradeoff.

Why More Data Usually Means More Problems

First, why even learn dimensionality reduction? Because if you cannot condense 500 job requirements into one human skill set in this economy, you might not survive the recruitment filter.

I probably overfitted that joke, but we’ll move on :)

The main purpose of dimensionality reduction is to make data less complex so the learning algorithm can understand it more meaningfully. In the real world, data is often messy and high-dimensional. For instance, if you have 300 features for a machine learning prediction, using every single one will often lead to low performance. Even if you remove the obvious weak features, the sheer volume of features can overwhelm the model with noise. This is often called the Curse of Dimensionality.

It is the same with image data. Think about a small 100x100 pixel grayscale image. That looks tiny, but to a computer, that is 10,000 features because every single pixel is a variable. If you are trying to recognize a face, most of those pixels are just background noise or redundant information. Using all 10,000 dimensions makes the math incredibly heavy and prone to overfitting.

For text, the problem is even more extreme. Every unique word in the dataset becomes a new dimension, meaning a simple document can easily turn into a feature vector with tens of thousands of columns. Most of these words are sparse or irrelevant, so dimensionality reduction is used to distill those thousands of words down to a few core topics that actually represent the meaning of the text.

Reducing the dimensions helps the model focus on the actual signals that matter rather than getting lost in the noise. It makes models faster and usually more accurate because they are not over-complicating the relationship between variables.

Picking the Right Tool for Dimensionality Reduction

In this article, I will briefly explain the intuition behind six major algorithms: PCA, LDA, SVD, t-SNE, UMAP, and Autoencoders. There won’t be too much math involved since the goal is to develop a geometric feel for how these tools actually function.

The best way to organize these methods is by their mathematical logic.

The Linear methods includes PCA, SVD, and LDA. These are excellent for simple and flat data structures. PCA and SVD are unsupervised, which means they analyze the data as it is. In contrast, LDA is supervised and requires labels to help separate different classes.

Then there are the Non-Linear methods like t-SNE and UMAP. These are unsupervised and perform better on curvy or complex data, making them ideal for data visualization.

Autoencoders represent the deep learning approach. They use neural networks to perform dimensionality reduction with significantly more flexibility and offer the ability to handle extremely complex data that traditional math might miss

PCA: Maximum Variance

Principal Component Analysis (PCA) transforms high-dimensional data into a smaller set of new dimensions by creating linear combinations of original features that still contain most of the original information. The core intuition here is to maximize the variance of the dataset.

Imagine a dataset in 3D space with three variables: $x, y,$ and $z$. Our goal is to transform this into a 2D plane. In a standard regression or a simple data mining approach, you might just keep the two variables with the highest correlation to your target. That is Feature Selection.

But PCA is Feature Extraction. We do not simply pick the best two original variables. We look for a new set of axes, which are linear combinations of the original features that capture the maximum possible variance.

Since we are working in a 3D space, we will have exactly three Principal Components. Why? Because PCA is essentially a change of basis. We are rotating our original $x, y, z$ coordinate system into a new $PC_1, PC_2, PC_3$ system. You can’t have more than three because you can’t find a fourth direction that is perpendicular to the first three in 3D space. You didn’t lose the dimensions yet, you just reorganized them.

The Geometry of a Principal Component

A Principal Component is just a fancy way of describing a new feature that is a weighted sum (linear combination) of your original ones.

This process begins by identifying the First Principal Component ($PC_1$). This is the specific vector in 3D space along which the data is most spread out. It represents the strongest signal in your dataset.

Once $PC_1$ is locked in, we find the Second Principal Component ($PC_2$). There is a mathematical catch: $PC_2$ must be strictly perpendicular (orthogonal) to $PC_1$. By being perpendicular, $PC_2$ ensures it captures only the remaining variance that $PC_1$ missed without any redundant overlap. Because they are orthogonal, the components are statistically uncorrelated.

Finally, $PC_3$ is the last perpendicular axis, capturing whatever tiny bit of jitter is left.

To put this in perspective, imagine your calculations for a 3D dataset show:

- $PC_1$ explains 95% of the variance.

- $PC_2$ (the perpendicular mix) explains 4%.

- $PC_3$ (the final perpendicular axis) explains only 1%.

Since we want to get only 2 features, we drop $PC_3$ since it doesn’t contain much information as it explains only 1% of the dataset. So we have effectively traded a 33% reduction (one out of the 3 dimensions has been removed) in data size for a mere 1% loss in information.

Scaling Up to Higher Dimensions

What happens when we move from our 3D example to a massive dataset with 100 features? The logic remains exactly the same, just harder to picture. PCA still finds 100 perpendicular components and orders them systematically based on the variance they carry.

Think of this as the 80/20 rule for data. In a 100 dimensional space, the first handful of Principal Components often capture the vast majority of the variance. The remaining components typically represent digital background noise.

To decide where to cut the dimensions, we look at the Eigenvalues. In geometric terms, an Eigenvalue is a number representing the length of a Principal Component.

We can create a Scree Plot by ranking these eigenvalues from largest to smallest. This allows us to see the exact point where the information plateaus. We keep the $k$ components that matter and discard the rest.

Determining the Value of k

When we move to 100 dimensions, we need a objective way to choose $k$, which is the number of dimensions we keep. This depends on the Cumulative Explained Variance.

In most data science workflows, the goal is to retain enough components to account for 70% to 90% of the total variance. If the first 10 components capture 85% of the variance, then $k = 10$. This allows us to discard 90 dimensions while losing only 15% of the actual information.

A Technical Summary of the PCA Process

Let me summarize the mechanics in a more techincal way. Principal Component Analysis reduces dimensionality by identifying the top $k$ principal components that capture the maximum variance while discarding the rest.

The mathematical process follows a specific logic

- We calculate the Covariance Matrix ($\Sigma$) to see how all 100 features relate to each other

- We perform Eigendecomposition on that matrix to solve the characteristic equation $\text{det}(\Sigma - \lambda I) = 0$ to find Eigenvectors and Eigenvalues

- The Eigenvectors ($v$) define the new directions for our data where each eigenvector is strictly perpendicular to the others

- The Eigenvalues ($\lambda$) represent the variance or power along those new axes

- We rank the components by their Eigenvalues to select the optimal $k$ based on the variance thresholds mentioned above

Projecting data onto the top $k$ eigenvectors preserves the core signal while reducing dimensions. This effectively compresses a mansion into a functional home without losing structural integrity.

LDA: Maximize Class Separability

If PCA is about retaining the highest variance, Linear Discriminant Analysis (LDA) is about finding the most distinction.

The fundamental difference is that LDA is supervised while PCA is unsupervised. But what does that actually mean in practice?

PCA is Blind But LDA is Not

When we talk about PCA, it is important to notice that the algorithm does not need any labels to do its job. Imagine you have a massive dataset of animal measurements but you do not know which data point belongs to a cat, a dog, or an elephant.

PCA is unsupervised because it is blind to these categories. It relies purely on math to find the directions of maximum variance regardless of what those points represent. It simplifies the data based on how much it spreads out, not based on what the data actually is.

LDA is supervised because it takes those animal labels into account. If you are trying to distinguish between different species, PCA might find a direction that explains the general size or weight of the animals. However, LDA will specifically hunt for the axis that maximizes the gap between the clusters.

I often think of this way. PCA looks at the whole forest and finds the direction where the trees are most spread out. LDA looks at the species of the trees and finds the direction that best separates the oaks from the pines

Essentially, LDA wants the clusters to be as far apart as possible from each other while being as tight as possible individually. This makes it a much more powerful tool when your goal is classification rather than just general data simplification.

The Intuition of the Gap

The idea of LDA lies in how it handles the noise within a group versus the signal between groups. It evaluates data based on two specific goals

- Maximize Between-Class Scatter ($S_B$) which means pushing the centers of the groups as far apart as possible

- Minimize Within-Class Scatter ($S_W$) which means squashing each group into a tight, dense cluster

When you project high-dimensional data onto an LDA axis, you are looking for the view that creates the cleanest gap. This ensures that when a classification model looks at the data later, the boundaries between categories are obvious and distinct.

The Dimensionality Constraint of LDA

There is a hard mathematical limit to LDA that does not exist in other methods. You are strictly limited by the number of classes ($C$) in your dataset. The maximum number of dimensions LDA can produce is $C - 1$.

To understand why, think about the geometry required to separate objects

- To separate two groups, you only need to look at them along a single line. If you can find the right line, you can tell them apart.

- To separate three groups, you only need a 2D flat plane. Think of three points forming a triangle on a sheet of paper. You do not need a 3D box to describe their positions relative to each other.

This is why LDA is so aggressive with dimensionality reduction. If you have 100 features but only 3 categories of animals, the algorithm realizes that any information beyond two dimensions is redundant for the specific task of separation. It distills that entire 100D space down to just the two meaningful directions that actually define the gaps between your groups.

A Technical Summary of the LDA Process

The mathematical logic of LDA follows a similar matrix-to-axis flow as PCA, but with a focus on class scatter rather than global covariance.

The process follows this specific logic

- We calculate the Within-Class Scatter Matrix ($S_W$) to see how spread out the data is inside each individual group

- We calculate the Between-Class Scatter Matrix ($S_B$) to see how far the centers of the groups are from each other

- We perform Eigendecomposition on the matrix product $S_W^{-1}S_B$ to find the Eigenvectors and Eigenvalues

- The resulting Linear Discriminants ($LDs$) are the new axes that maximize the ratio of between-class variance to within-class variance

- We rank these by their Eigenvalues and keep the top $k$ components where $k$ is less than or equal to $C-1$

While PCA is a general-purpose tool for simplifying data, LDA is a targeted tool used when you know exactly what categories you want your model to distinguish.

SVD: Discover Latent Structure

Singular Value Decomposition (SVD) is a fundamental matrix factorization method that decomposes any $m \times n$ matrix into three constituent matrices. It uncovers latent structure, which refers to the underlying patterns linking features and observations that are not explicitly labeled.

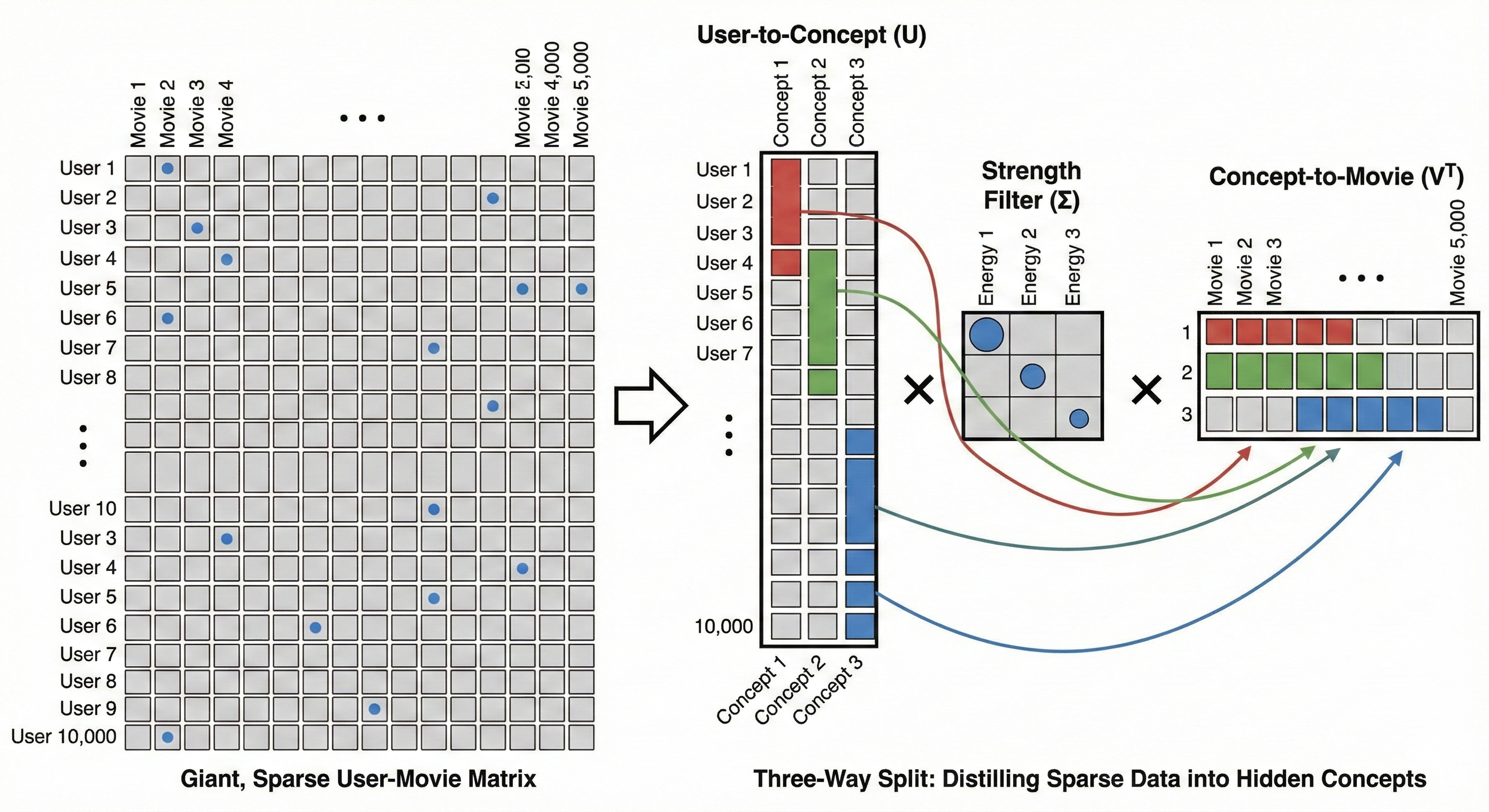

In recommendation systems, SVD performs a low-rank approximation. For example, in a movie streaming service, the raw data is a sparse matrix where rows are Users and columns are Movies. SVD identifies Latent Factors, which are hidden categories like Explosive Action or Nostalgic Vibes discovered through user interactions. What are these exactly? No idea as I just made them up but the point is to convey that there are hidden genres that humans can typically classify.

SVD identifies these traits mathematically and compresses the sparse data into a lower-dimensional set of features. This allows the system to predict what a user will like based on their proximity to certain latent factors, essentially capturing the essence of their taste.

The SVD Mechanism

Imagine a massive table of 10,000 users and 5,000 movies. The goal is to understand what people actually like. Most of the table is empty because no one watches everything. This is a sparse matrix. If you try to analyze it as is, you are looking at a giant map. SVD looks at this map and realizes that you do not need 5,000 movie columns to understand a user. You only need to know how that user relates to a few latent factors.

SVD performs a three way split to find these hidden categories.

The User Map ($U$) groups users who share the same vibe. Instead of looking at 10,000 individuals, SVD sees how each person aligns with the hidden latent factors.

The Strength Filter ($\Sigma$) identifies which of these hidden factors actually matter. It ranks them by energy. In this context, energy is the mathematical weight of a pattern. If 8,000 users all watch similar fast-paced movies, that pattern has high energy. If only two people watch a specific niche film, that is low energy noise. We keep the high energy factors and discard the low ones to filter out the jitter and focus on the real signals.

The Content Map ($V^T$) groups the movies by those same hidden concepts.

This is how SVD discovers patterns like the Explosive Action mentioned earlier. The algorithm does not know these words, but it sees the mathematical connection between a group of users and a group of movies. The system can recommend a film you haven’t seen yet by focusing on these high energy latent factors because it sits in the same mathematical bucket as your favorites.

The Geometry of SVD

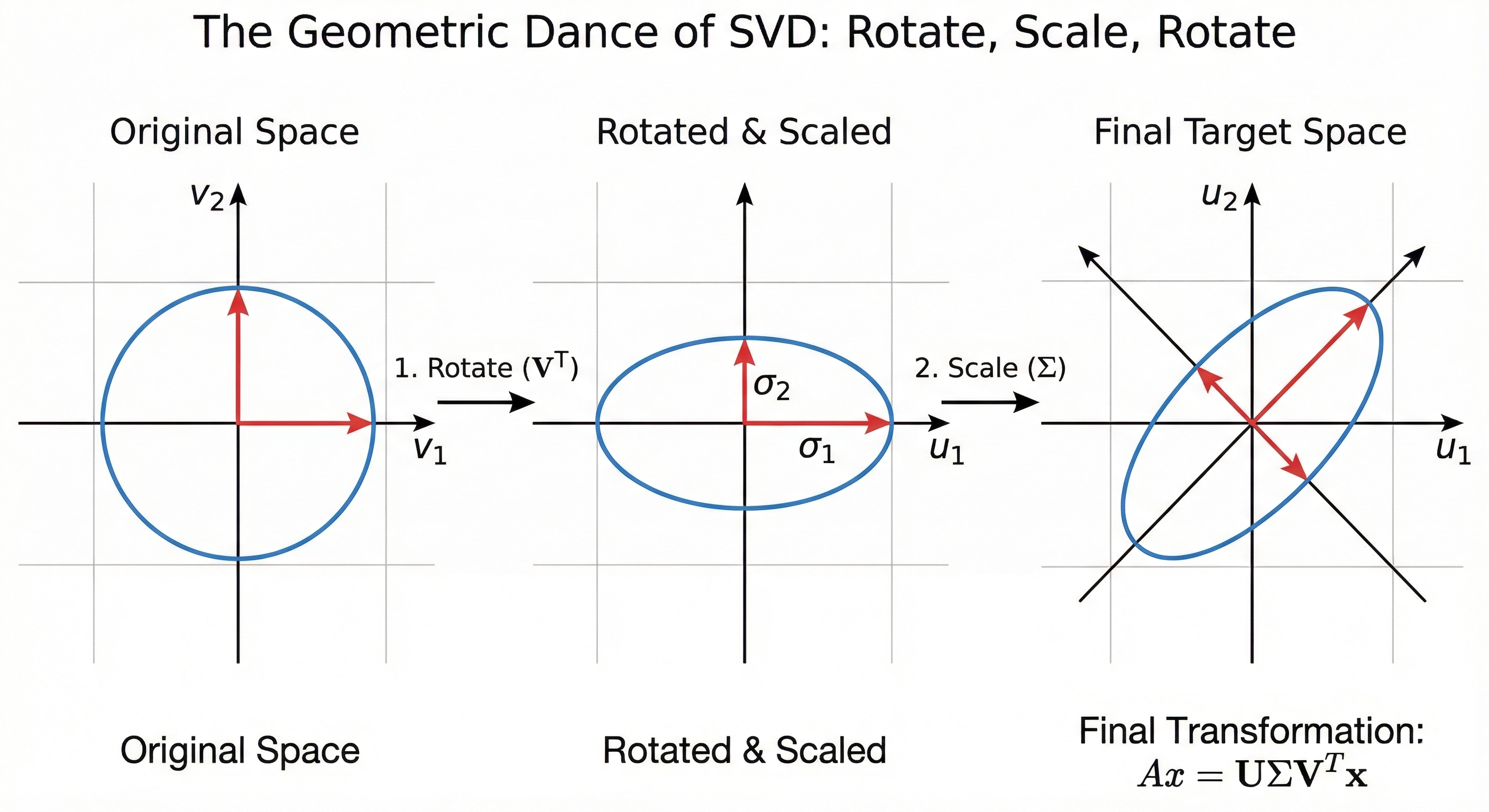

While the User Map and Content Map help us see the data as tables, the underlying math is performing a geometric dance. If you imagine your data as a cloud of points floating in a high dimensional space, SVD is the process of finding the primary axes of that cloud.

SVD tells a story of how a standard circle is twisted and stretched into the complex shape of raw data through three movements. First, Rotate ($V^T$) turns our perspective like a camera to align with the natural tilt of the data without changing its shape. Next, Scale ($\Sigma$) uses Singular Values to stretch axes with high energy signals and squish those representing noise, transforming the circle into an elongated ellipse. Finally, Rotate ($U$) takes this simplified, essential shape and rotates it into the final coordinate system of our rows to map core concepts back onto the original players in the dataset.

Think of the Singular Values in the $\Sigma$ matrix as the length of these axes. The first and largest value represents the direction where the data is stretched the most, capturing the strongest signal. As you move to smaller values, the axes get shorter and shorter until they eventually just represent tiny jitters of noise.

We are effectively flattening the data cloud into a simpler shape by keeping only the longest axes, . This is why it is called a low-rank approximation. We are intentionally squashing the dimensions that do not matter to highlight the ones that do. It is like taking a complex, 3D sculpture and finding the perfect 2D shadow that still tells you exactly what the object is.

SVD vs. PCA

In data science, the shape of data matters. While many statistical methods assume square matrices (where rows equal columns), real-world data is almost always rectangular (e.g., 10,000 customers vs. 20 features).

One fundamental difference lies in data preparation. PCA via Eigendecomposition requires a square and symmetric matrix. Specifically, it operates on the Covariance Matrix $X^T X$. SVD is a more flexible factorization tool. It can be applied directly to the original $m \times n$ rectangular matrix $X$ without needing to transform it into a square format first.

PCA is designed to find Principal Components with the highest variance. While SVD is often used to compress a matrix to a smaller size, its purpose in PCA is more specific. SVD decomposes a matrix into Singular Values which represent the importance or energy of each dimension. If you center your data by subtracting the mean, the results of SVD and PCA become identical. The Right Singular Vectors from SVD become the Principal Components of PCA. This means SVD reaches the same statistical goal as PCA but uses a different mathematical path.

Most modern data science libraries like scikit-learn use SVD as the underlying mathematical engine to compute PCA. It is a misconception that SVD prepares data for PCA. Rather, SVD replaces the need for the computationally expensive and numerically unstable Eigendecomposition of a covariance matrix. SVD identifies the same principal components by decomposing the rectangular data directly. This avoids the precision errors that happen when you square the data to create a covariance matrix.

A Technical Summary of the SVD Process

The mathematical logic of SVD allows it to handle any matrix regardless of shape while bypassing the instability of squaring data.

The process follows this specific logic

- We take an $m \times n$ matrix $A$ and factor it into the product of three specialized matrices $U$, $\Sigma$, and $V^T$

- Left Singular Vectors ($U$) define the new coordinates for our rows. These are the eigenvectors of $AA^T$ and represent how much each row belongs to a latent factor

- Right Singular Vectors ($V$) define the new coordinates for our columns. These are the eigenvectors of $A^TA$ and represent how much each column belongs to a latent factor

- Singular Values ($\Sigma$) are the square roots of the eigenvalues found in the previous steps. These are ranked from largest to smallest to represent the energy of each factor

- Dimensionality Reduction occurs when we keep only the top $k$ singular values. By ignoring the rest, we reconstruct a version of the matrix that preserves the core signal while discarding the background noise